When the government can read your mind

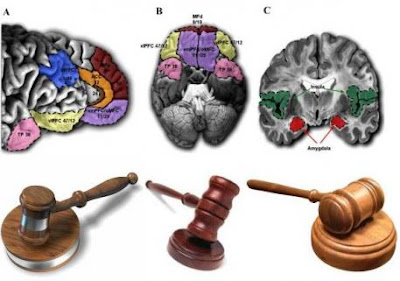

We are now at a point where we can scan brain activity with fMRI, decode the patterns, and use the information to “read minds” or predict what a person is experiencing. For example, the Gallant Lab at the University of California, Berkley , published a paper in 2011 1 showing that by recording subjects watching a set of movies, they can estimate what visual features parts of the brain are encoding. Then, when they show you a new movie, their model can predict what you are seeing based on your brain activity. This “mind-reading” has limitations: the reconstruction is primitive, worse on abstract or rare stimuli, and each subjects must be scanned many times to tune the model to his or her individual brain. However, this experiment proves the principle that we create models that use brain activity to predict dynamic conscious experience even with the low visual and temporal resolution and indirect measures of an fMRI. Other labs are progressing in different domains, for example Chang and...